Interview with Christine Vernay, Domaine Georges Vernay

Interview with Christine Vernay 5th March 2020 at Domaine Georges Vernay

Edited for clarity and brevity

How would you describe a Condrieu to someone who has never tasted one?

Viognier is an aromatic variety by definition. In Condrieu, this aromatic side is much less exuberant, much less pronounced. There’s a complexity compared to Viogniers from other parts of France or abroad, which display more of this exuberant side.

To describe a fairly classic Condrieu, on the nose you’ll find strong apricot notes, white peach, stone fruit and white flowers. On the palate, you find these apricot and white flower notes again, more or less clearly depending on the vintage. You often find pear aromas as well, more during fermentation than in the finished wine.

In certain terroirs such as the Coteau de Vernon you can still find floral notes but also citrus, thyme. I’m exaggerating a bit, but you almost lose the grape variety on terroirs like this with old vines – terroir has a very strong influence over the variety. On the Coteau de Vernon where I’ve just been replanting some vines, I was impatient to vinify the fruit from these new vines to see if the terroir speaks even in youth.

And the result?

The terroir speaks. Not with the same depth as the old vines or the same structure on the palate, but there’s a similar identity. That was a discovery for me, a real test of the greatness of nature. I’ve never found the same expression as Vernon in my other vineyards, even in my 50-year-old vineyard for Terrasses de l’Empire.

And how about the sensation of tasting a Condrieu, on the palate?

There’s a repeat of what you find on the nose, but also these quite unctuous notes, this glycerol, it’s full-bodied. Depending on the terroir, it’s more or less elongated in shape. For a great wine, you need an elongated shape – if it stays round, it’s not enough. I like to talk about the shape of a wine; you can have square-shaped wines, round shapes, triangular, oval. Condrieu, especially on Vernon or the Chaillées d’Enfer, on particular terroirs, you can find this oval shape… I think it’s one of the characteristics of Condrieu.

With a classic Condrieu you find apricot and floral notes on the palate but I find this less with old vines, which have an intense complexity – less characteristic of the variety but a more detailed aromatic palate. You can have notes of citrus, bergamot, sometimes notes of thyme, lemon thyme. After that there can be exotic notes, lychee, things like that.

Can you say that even a young Condrieu is a complex wine?

Yes, even for a classic Condrieu, but this complexity is accentuated by the terroir. And terroir isn’t just the subsoil, it’s a lot of other things. When we talk about terroir we’re essentially talking about soil, but also the way in which the vines are grown. The way of working, and the man or woman that accompanies this terroir, is also important. To channel terroir you have to be there to guide it. But at the same time, I’m not a not a magician. I can’t convert something that doesn’t already exist. I often make the comparison with the education of a child. The aim of education is to help a child grow, but with a vine or a wine it’s to understand it, in order to help it become what it can be.

I notice you haven’t used the term ‘minerality’.

For me that’s something very abstract. It’s often confused with acidity, when we speak about minerality it’s often about wines with quite pronounced acidity. I use the term very rarely, it doesn’t have a very clear definition for me. A word I use more often when describing Condrieu is ‘salinity’ because it’s a wine that doesn’t have acidity, it’s characterised by this lack of acidity. But Condrieu terroir can generate a saline effect. It’s a term we can agree on because it has a physical reaction: salinity is something that makes you salivate. And despite the lack of acidity, a Condrieu should have this mouth-watering effect. It’s not acidity, but it creates a feeling on the palate.

Is this salinity something you can emphasise when you make the wine?

It’s the whole process of winemaking, to create balance, and this salinity is part of the balance. But one particular process? I don’t think so.

To buy a copy of my latest book, Wines of the Rhône, please click here.

Interview with Jean-Paul Jamet, Domaine Jamet

To celebrate the publication of my new book, Wines of the Rhône, on 25th January, I'll be published a series of interviews with some of the most influential winemakers in the Rhône Valley, starting with this interview with Jean-Paul Jamet.

Interview with Jean-Paul Jamet 2nd March 2020 at Domaine Jamet

Edited for clarity and brevity

What are the different styles of Côte-Rôtie?

The soils have a strong bearing on the style of the wine. If a particular vigneron has this or that style, it’s often based on the terroir they have, the geographical location of their parcels. Those who have vineyards in the south of the appellation at Tupin, generally speaking the wines will be more elegant and charming, have more finesse. On the other hand, on the schist side – and there are various types of schist, some with a more floral, fruity, spicy expression, others having a more graphite side – they give wines that take longer to come around, that need a more careful élevage. After that, the approach of the winemaker can compensate, rebalance or bring out these characteristics.

And is that in the vineyard or in the cellar?

I’m thinking more about the cellar, with the vinification. It was fashionable to destem in the 1990s. Today we’re not so excessive in terms of destemming.

Was it traditional to use whole bunches?

In the cellars of old vignerons, I’ve seen old corking machines, old pumps, old tools but I’ve never seen on old destemmer. In Hermitage it would seem there were rudimentary old destemming machines. I wouldn’t say they’ve never existed here but I’ve never seen one in Côte-Rôtie.

Where did the practice of destemming come from in Côte-Rôtie?

It was really commercial considerations that encouraged winemakers to remove stems, because they brought a lot of imperfections with them. They do bring certain qualities too – but qualities that take time to become apparent. So destemming in the 1990s made wines that were more forthcoming, more accessible, more juicy, more flattering when young.

And it was scores – critics giving high scores to accessible wines that were then polished by new oak. It makes for impressive wines. But you lose the soul of the terroir.

I never changed my way of working. I’ve stayed within the small percentage of winemakers that stayed traditional. At the start of the 1990s, I was atypical for the appellation in fact. Everyone else was destemming and I was one of the rare winemakers not to. The only vintage I totally destemmed, paradoxically, was 2003. Since the start of the 90s I’ve had no destemmer, so it’s been 100% whole bunch.

Destemming was useful – and in certain cases it was needed. But today, lots of vignerons are starting to work with stems again.

Why did everyone suddenly think that more extracted wine was a good thing?

Because of scores from critics. I’m sorry to put it so bluntly, but it was chasing scores. When you destem and extract more, you get wines that are darker in colour, that are more tannic so they’re more impressive. Except they are less pleasurable; with more extraction you lose aromatics. It’s for each vigneron to ask themselves whether they want to follow fashion, or whether they want to make the kind of wines they want to make.

And what about new oak barriques?

It was all in the same period - destemming, extraction, new oak and – bang – you have a 99 out of 100 points – fantastic! Do you want to drink a bottle? No. But commercially, if you have a good score, you sell well in certain markets. It’s sad, but that’s how it is. It’s an approach, I’m not condemning it.

What are the most important points to take into account when making wine with whole bunches?

One thing is sure: when you’re working with whole bunches, you have to pick the grapes at a good level of ripeness, so you have to wait for longer before picking, which is a risk. With the destemmer you can harvest a week earlier and you’ll make a very good wine. It can snow, it can hail, whatever – the grapes are picked. Sometimes you can’t wait, and in that instance the destemmer has its place, it’s a good tool, but not one to use every year. In powerful, rich vintages such as 2019, when using whole bunches, you can drop 0.6% or 0.7% in potential alcohol.

Is that from dilution?

There are two effects; a bit of dilution from the water in the stems, and the stems absorb alcohol. You also lose a little colour; you lose a little acidity. But I find that brings another dimension to the wine. Often, I say when you use destemmed grapes you make a lovely Syrah, but when you use whole bunches you make a Côte-Rôtie. Because there are different balances linked to this vegetal component, which after some time, is no longer tastes vegetal.

Do stems help bring the terroir to the fore?

I’m convinced of it. In our tanks the vinification is often very similar, but there are big differences in the finished wines. For me, it’s more marked with those with stems. It’s my belief, but in wine there are no absolutes – it’s just my belief.

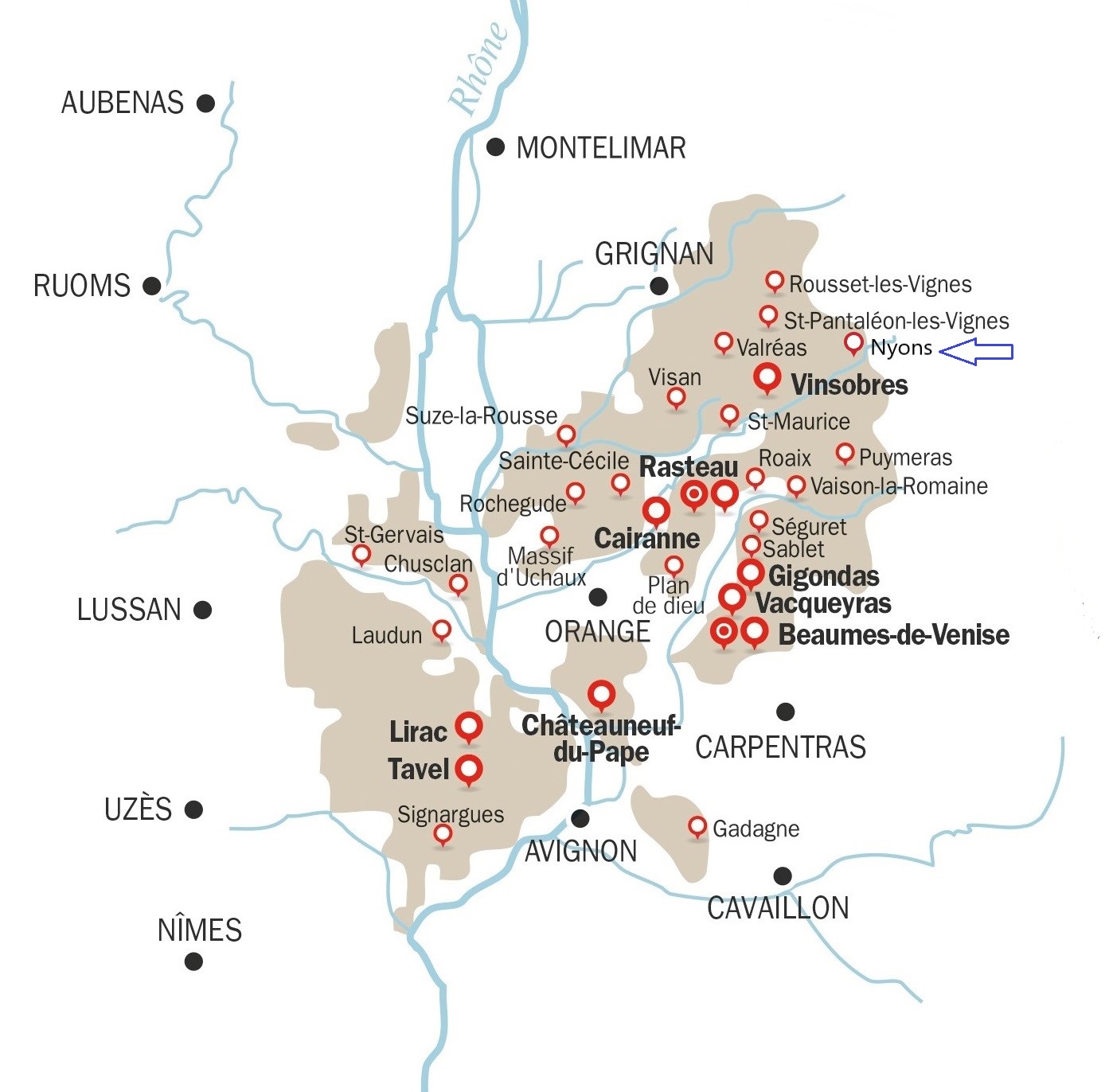

2019 Rhône Report out now on Decanter Premium

With rolling travel restrictions and intermittent lockdowns this year, I was lucky to be one of the few Rhône specialists to taste the new vintage in situ this year. I spent two and a half weeks tasting over 1,300 wines from every cru in the Rhône Valley, both north and south. This is an extreme vintage, one marked by record temperatures and parched conditions, that has – where winegrowers have played their hand well – resulted in some exceptional wines.

In the Southern Rhône this is a particularly thrilling year for Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The best wines are concentrated, intense and powerful with abundant velvety tannins and – perhaps surprisingly – good levels of acidity. Some estates have produced some of their most impressive wines to date. But there are also countless overripe wines with unbalanced that lack freshness. Outside Châteauneuf, quality is less reliable, but it’s another very good year for Gigondas, not to mention other fresh terroirs such as Vinsobres. Whites, too, are better than I expected considering the uncompromising growing season.

The Northern Rhône is very good in places – especially Côte-Rôtie and the northern reaches of Saint-Joseph. As you travel towards the southern pole, the heat becomes more problematic, especially around Cornas. Hail devastated parts of Crozes-Hermitage, but thankfully it didn’t hit Hermitage, which has produced some majestic wines, both in reds white.

For a detailed breakdown of every appellation and notes on 450 wines, visit Decanter Premium www.decanter.com (paywall) over the coming week. An edited version of the report will also appear in the magazine, spread across two editions in early 2021.

Images of Nyons

Nyons is the newest Named Village in the Rhône, since October 2020. I visited the area in 2019, but didn't take any photos as I didn't know it was going to be promoted at this stage! The following are images supplied by the Syndicat des Vignerons du Nyonsais. For the sake of completeness, I wanted to include some images on this site - it would be a shame to have photos of every appellation in the Rhône apart from one... I'll add further images of the people and terroir after I visit next year.

Images of the Diois

There are four appellations in the Diois: Clairette de Die (which equates to around 95% of all AOC wine), Crémant de Die, Coteaux de Die and Châtillon-de-Diois.

AOC Châtillon-en-Diois, in the far east of the region, makes still whites, reds and rosés from Burgundian varieties (and some Syrah).

Olivier Rey, president of co-operative Jaillance, which makes over 70% of AOC Clairette de Die, a sparkling white wine, usually sweet, made from at least 75% Muscat à Petits Grains Blancs and no more than 25% Clairette.

Marl vineyards at the centre of the Diois.

The other principal soil type is colluvial limestone scree.

Fabien Lombard of Domaine Peylong, one of the six producers to make AOC Coteaux de Die, a still, dry white made from 100% Clairette.

It was grey and wet when I visited, so here is a photo taken in sunnier conditions of Suze-sur-Crest © Juan Robert.

Images of Châteauneuf-du-Pape

The village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape viewed from the east

Châteauneuf-du-Pape, with the ruined château in the background

The village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape - smaller and quieter than you might expect

Morning in Châteauneuf-du-Pape

The cellar of Château de Beaucastel

Blending at Château de Beaucastel

Emmanuel Reynaud of Château Rayas (taken 2015)

Jean-Paul Daumen of Domaine de la Vieille Julienne

Christophe Sabon of Domaine de la Janasse (taken 2016)

Didier Negron of Domaine Roger Sabon (taken 2015)

Joris Laget and Daniel Chaussy of Mas de Boislauzon

Jean-Paul Versino of Domaine Bois de Boursan

Matthieu Faurie-Grépon of Mas Saint Louis

Véronique Maret of Domaine de la Charbonnière (taken 2015)

Stanislas Wallut of Domaine de Villeneuve

Laurent Brechet of Château de Vaudieu

Vincent Estevenin of Domaine de Marcoux (taken 2016)

Jean-Claude Vidal of Domaine du Banneret

Tastevin at Domaine du Banneret

Henri Bonneau (1938 - 2016) (taken 2014)

Henri Bonneau's yard

Vineyards in the north of Châteauneuf-du-Pape near Rayas

Sunset at the château

Châteauneuf-du-Pape at dusk

Images of Cornas

The village of Cornas

Largely east-facing slopes at the southern part of the appellation - lieu-dit Combe on the left, lieu-dit Patou on the right

Olivier Clape, with lieu-dit Sabarotte in the background

The slope in the background features the south-facing lieu-dit Reynard (left side, in shadow) and the west and south-facing lieu-dit La Geynale (spread around the pyramid-shaped hill to the right)

Soils here is decomposed granite, the rocks easily crumble in your hands to coarse sand

The view to the south-east towards the ruined Château de Crussol in neighbouring Saint-Péray

Ploughs, presses and tanks in Thierry Allemand's winery

Thierry's son, Théo Allemand

Olivier's father, Pierre Clape

Bottles in the cellar at Domaine Clape

Images of Hermitage

The south-facing hill of Hermitage; the lower part is lieu-dit Les Bessards, the upper part is lieu-dit l'Hermite with the 'chapel' on top.

Standing in lieu-dit Les Greffieux, looking up at lieu-dit l'Hermite to the left, lieu-dit Le Méal to the right

Never-ending wall building and upkeep

The front of the chapel

The wine named after it

Caroline Frey, current owner of Paul Jaboulet Aîné

Domaine Marc Sorrel Hermitage rouge 'Le Gréal' - a contraction of the names of two lieux-dits: Les Greffieux and Le Méal

Marc Sorrel (taken 2015) retired in 2019, handing over the estate to his son Guillaume

Bernard Faurie

Faurie's tiny cellar underneath his house

Jean-Louis Chave (taken 2016)

How roots grow through granite on Hermitage

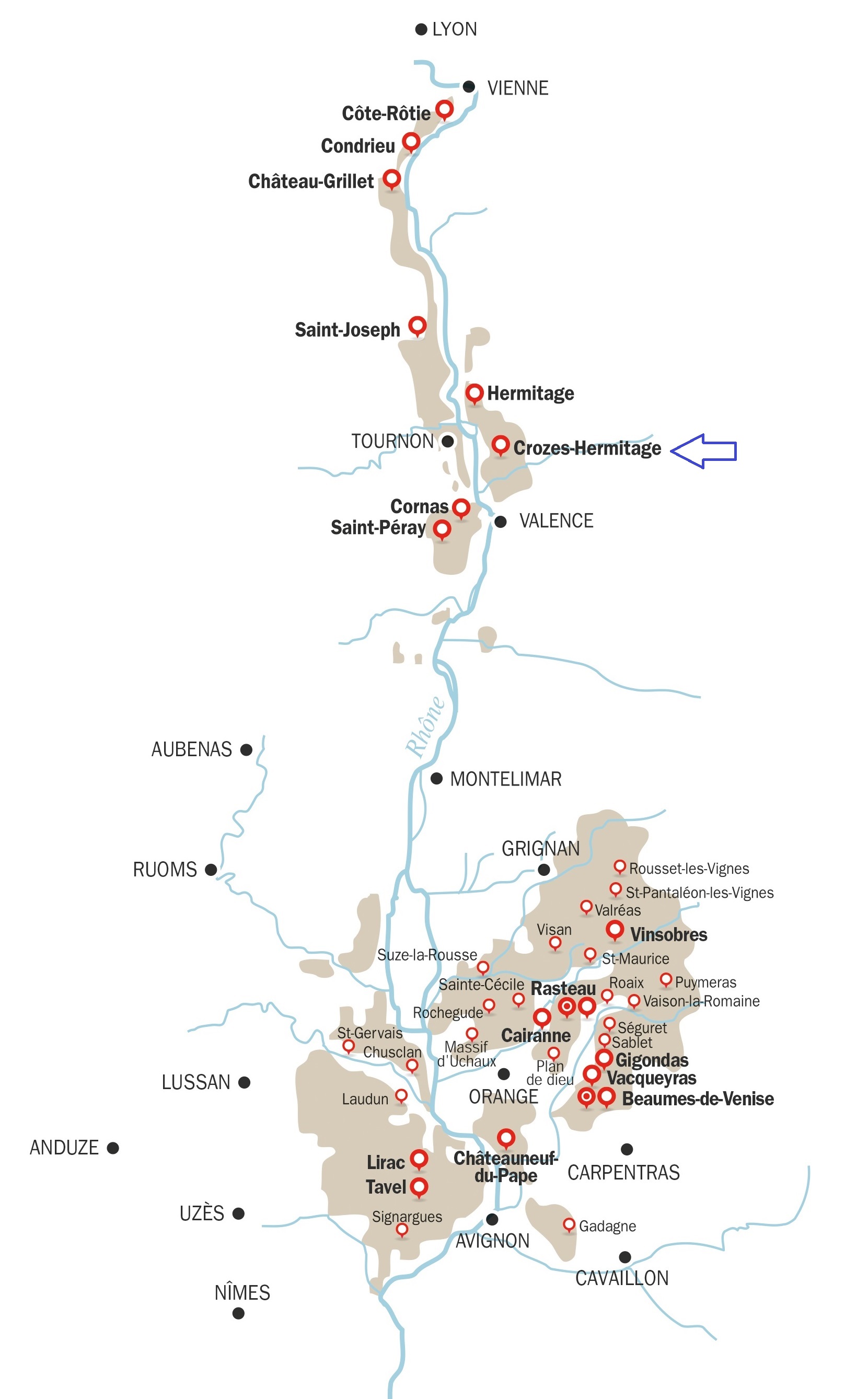

Images of Crozes-Hermitage

Standing in one vineyard, looking up at another - the southern part of Crozes-Hermitage is a series of alluvial terraces

Classic pebbly alluvial soils of the southern part of Crozes-Hermitage

David Reynaud (taken 2013)

Gaylord Machon

Emmanuel Darnaud (taken 2015)

Alain Graillot (taken 2014)

To the north of Hermitage, the terroir is very different, more sloping, with different soils types. These are fine, white clay soils known as kaolin in Larnage.

Laurent Habrard in Gervans, the northern part of the appellation

Laurent Fayolle of Domaine Fayolle Fils et Fille (taken 2017)

René-Jean Dard of iconic Natural wine producer Dard et Ribo

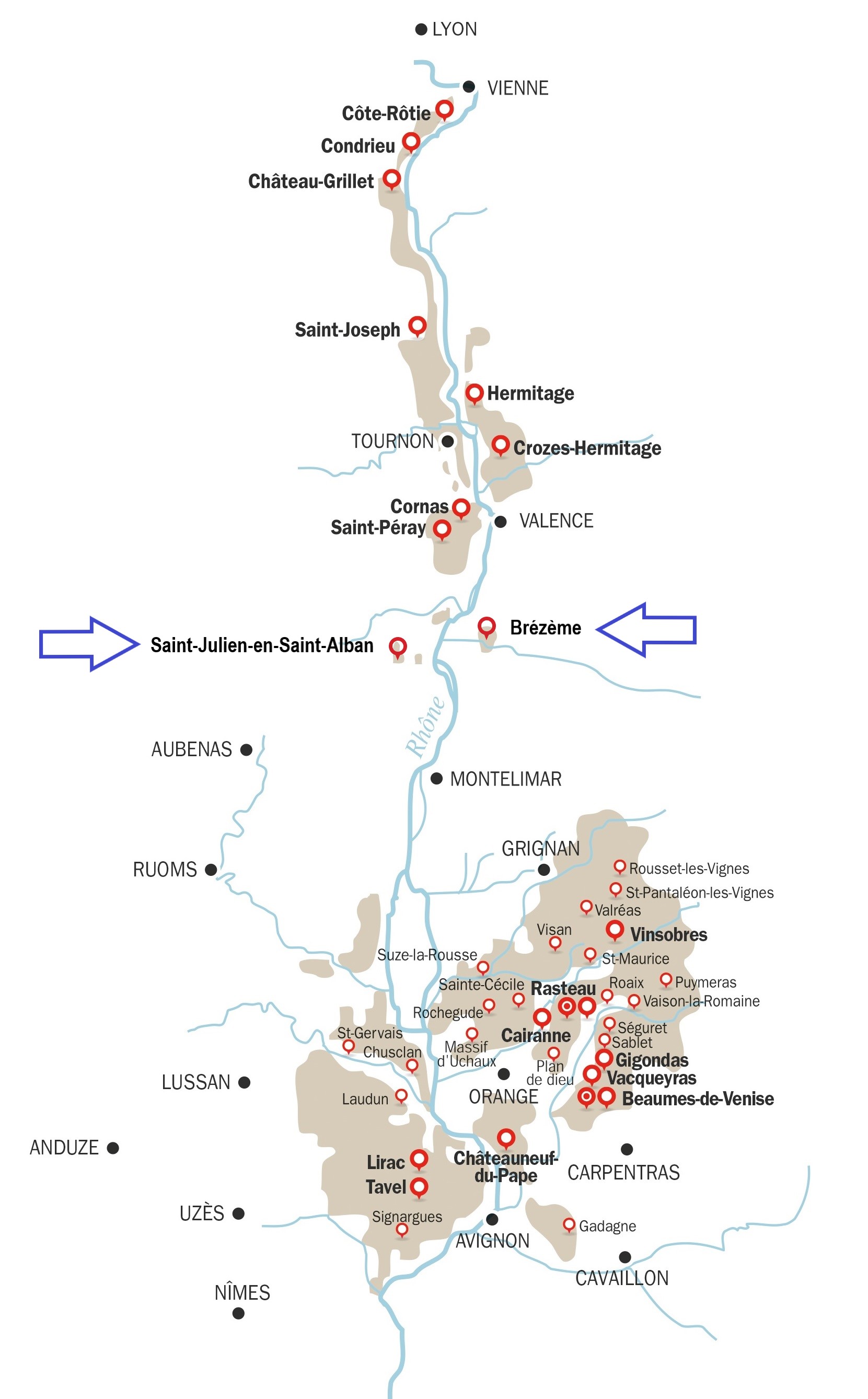

Images of Brézème and Saint-Julien-en-Saint-Alban

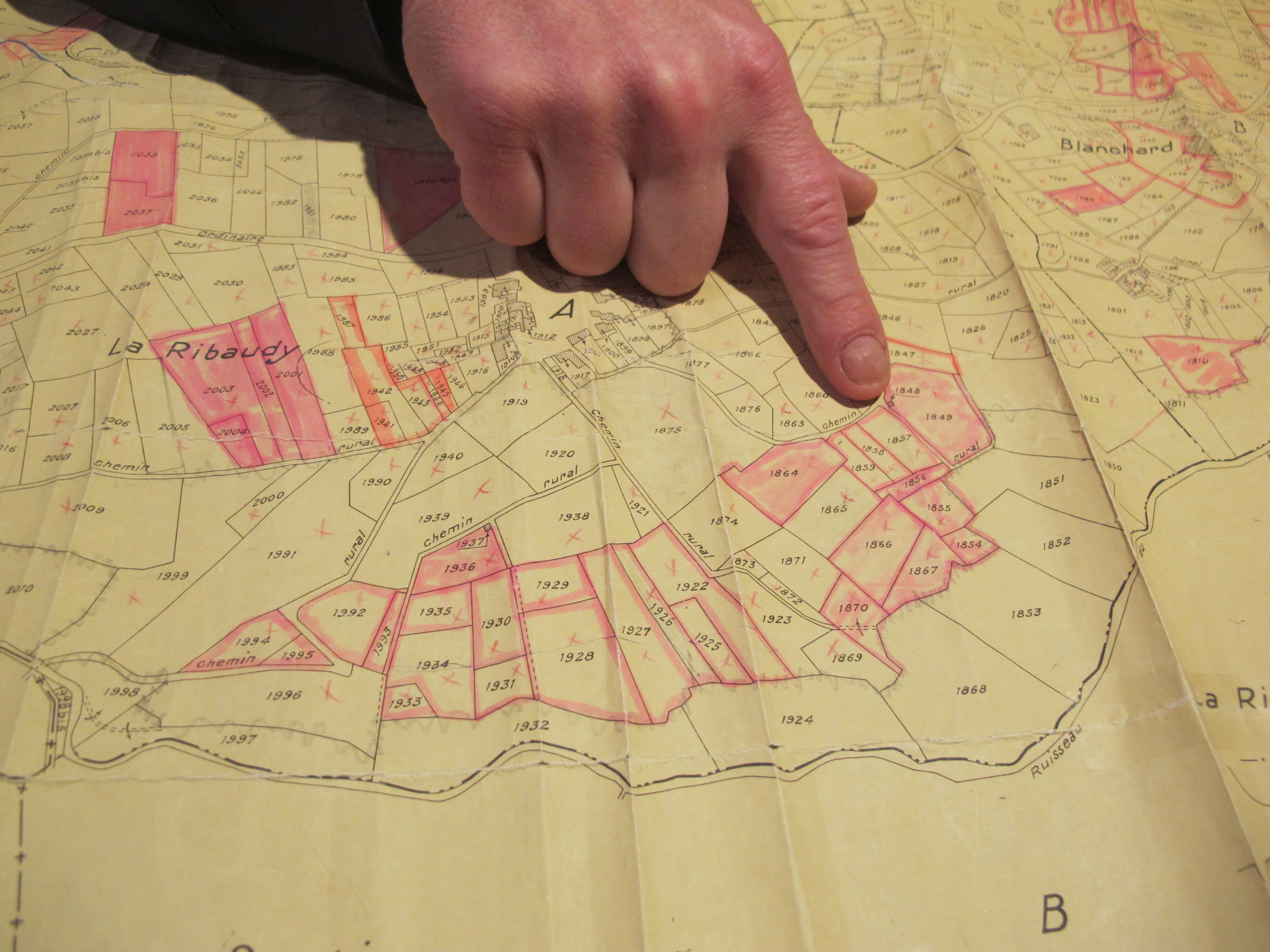

Officially these are AOC Côtes-du-Rhône vineyard areas, but use of the names either Brézème or Saint-Julien-en-Saint-Alban are tolerated on labels.

Looking south-east over the gently sloping clay limestone vineyards of Saint-Julien-en-Saint-Alban on the west bank of the Rhône

Looking west along the foot of the limestone hill of Brézème on the east bank of the Rhône

Charles Helfenbein

There are two other sub-regions within Brézème after the hill of Brézème itself, both of which have pebbly sand soils: Le David and La Rolière (pictured, looking north towards Saint-Péray on the other side of the Rhône)

Mathieu Piedade, winemaker at Château la Rolière, with the mountain range of Les Trois Becs dimly visible in the background to the left

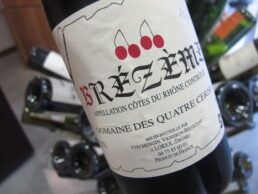

Yves Mengin of Domaine des Quatre Cerises, who started replanting the hill of Brézème after it had largely been abandoned. His project began in 1984, and his first vintage was 1998.

Domaine des Quatre Cerises rouge