Images of Tavel

AOC Tavel - 100% rosé.

Limestone soils to the west of the village known as Lauzes

Raphaël de Bez, Château d’Aquéria, joined his father and uncle at the estate last year

Christian and Nadia Charmasson of Balazu des Vaussières, whose natural Liracs and Tavel are now in Vin de France

Les Vignerons de Tavel, cave co-operative

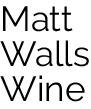

Beaumes de Venise: the hidden red of the Southern Rhône

Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge – and her sister, Pippa. Andy Murray – and his brother, Jamie. Beyoncé Knowles – and her sister, Solange. Having a more famous brother or sister can be a mixed blessing. On the one hand, it brings the benefits and opportunities of a star-studded surname. On the other, cynics may doubt the depth of your talents and it’s hard to escape the shadow of your sibling. So it is with Beaumes de Venise. Most wine lovers have heard of their sweet Muscats: not so many their reds. But they deserve a share of the limelight and there’s one estate in particular with an undeniable star quality.

One of the most beautiful places to make wine in the Southern Rhône is around the Dentelles de Montmirail, a high limestone outcrop topped with rows of jagged grey teeth not far from Mont Ventoux. Skirting around its base, you’ll find pretty Gigondas to its northwest and Vacqueyras to its southwest. Keep following it round to its most southerly point and you’ll find the village of Beaumes de Venise. With such celebrated reds being made nearby, you have to ask – what’s with all the Muscat?

Sheltered from the rampant north wind, Beaumes de Venise has a particularly hot microclimate – and Muscat loves the heat. It’s also particularly at home in the deep sandy soils near the village. (Surrounding hills are made from this compacted sand, it’s so soft you can find little grottos carved out of them – the name Beaumes comes from balma, the Provençale word for cave). It’s the perfect terroir for making sweet Muscat, a style that was once celebrated, but has since fallen out of fashion.

But most of the red grapes aren’t grown here. They’re planted higher up in the hills amongst dense woodland, in cooler sites, on different soils. At its highest point it shares a border with AOC Gigondas. Stylistically, however, the reds aren’t as polished and pure; they’re more like a musclebound Vacqueyras in need of a shave.

Beaumes de Venise Rouge can be gruffly tannic, deeply concentrated and potently alcoholic. Sometimes it’s all three of these things, but quality, though inconsistent, is climbing. When winemakers find methods of reining it in, the results can be impressive. Domaine de Fenouillet, Ferme Saint Martin, Domaine Martinelle, Domaine Saint Amant and Domaine la Ligière are all making fresh, bright wines without trying to efface its naturally broad frame and rugged character. And one producer in particular is making a wine that deserves wider renown.

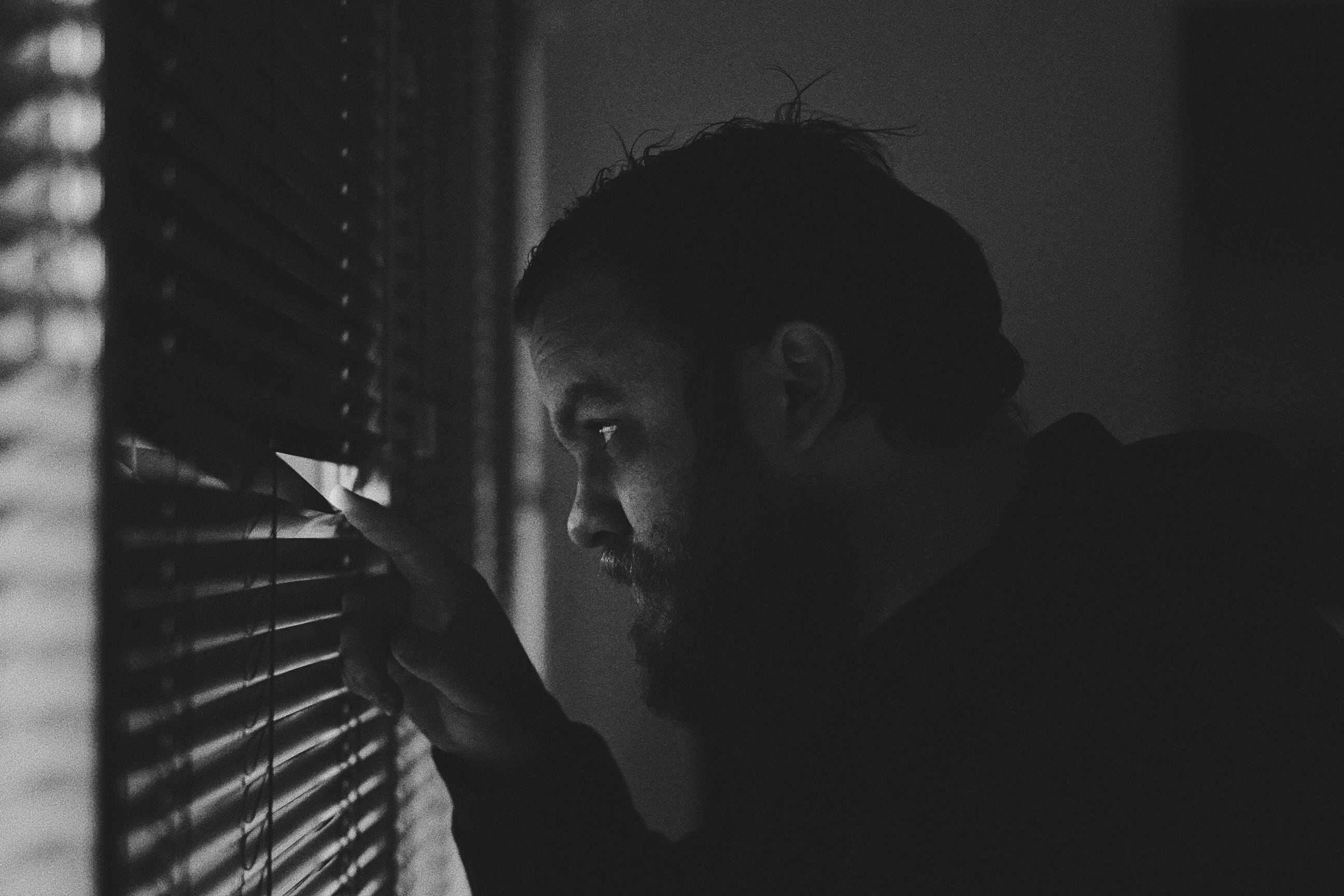

Domaine des Bernardins can trace its roots back to the 1500s. Romain Hall’s family have owned the estate since 1820. Reserved but welcoming, Romain represents the seventh generation making wine here. His great-grandfather Louis Castaud was instrumental in securing the AOC for Muscat de Beaumes de Venise in 1945 – not long after Châteauneuf-du-Pape, the daddy of them all. They’ve long been considered one of the best estates for long-lived sweet Muscat (their 1987 was outrageously good when I visited), but its time they were equally fêted for their red.

Their Beaumes de Venise Rouge is no wallflower but wields its power relatively lightly, with enduring aromas of Provençale herbs and black pepper over vibrant forest berry fruits. What makes it stand out amongst its peers however is twofold; its consistency of style and quality and its ability to age.

Some would describe the style as a little old-fashioned, and it’s fair to say their winemaking isn’t exactly hi-tech. For a start they don’t remove any stems from their red grapes, and this has a conspicuous effect on the style, adding freshness and interest to the texture and aromatics, and helping to moderate alcohol levels. They co-ferment varieties in raw concrete tanks for 15 days, then the wine spends a year in steel tank before release. There’s no oak involved in the process.

Romain is keen to stress that “we don’t seek overmaturity or overextraction, we look for finesse, freshness and acidity.” They have a wealth of old vine material and they pick relatively early. Maceration is gentle – no punching down, just wetting the cap. It all adds up to a restrained and balanced example of what can be a domineering style of wine.

I paid them a visit in January and Romain opened seven vintages: 2017, 2015, 2013, 2009, 2005, 2000 and 1995. Today the blend is 55% Grenache, 35% Syrah, 5% Mourvèdre and 5% Grenache Blanc – before 2015 it was two-thirds Grenache, one-third Syrah. Aside from that, nothing much has changed in its makeup over the years aside from the picking date – it’s three weeks earlier today than it was in 1995 to adapt to the changing climate.

The 2017 and 2015 were as good as their fantastic 2016, three excellent vintages in a similar vein of bright fruit with dried herbs, all subtly different, but equally fresh and balanced. The 2013 doesn’t quite have the fruit to match the stalk influence, but the 2009 and 2005 certainly do, two warm vintages that are still in great shape: the 2009 incredibly youthful still, the 2005 in comfortable maturity, with autumn leaves, liquorice and menthol woven through the deep, rich melted berries. The 2000 is tannic still but in decline, earthy with iron and dried blood. But the 1995 hangs on, with raspberry leaf, dried flowers and sage notes to its remaining dab of strawberry fruit. It still contains some tannic bristle, and approaches the end of its long life with a peppery sigh.

“Muscat is our baby, but we love making reds,” says Romain. Their sales of Muscat are stable, but they’ve doubled production of Beaumes de Venice Rouge in the past 10 years to 25,000 bottles a year. You can pick it up in France for €12.50 (Les Passionnés du Vin), in England for £15.20 (Tanners). It feels distinctly undervalued compared to top Vacqueyras and Gigondas. I wouldn’t expect it to stay this cheap forever.

“It’s hard for consumers to understand that two completely different wines come from the same terroir,” says Romain. But as tastes continue to move away from sweet wines toward dry ones, it’s time for Beaumes de Venise Rouge to step out from behind it’s golden sibling, and to be known for its own considerable gifts.

First published on timatkin.com.

Images of Rasteau

The village of Rasteau, on a south-facing slope.

The cliff running down to the river shows the three types of clay: a thin layer of red clay, followed by deep yellow clay, followed by deep grey (sometimes called blue) clay.

The Coulon family of Domaine de Beaurenard in Châteauneuf-du-Pape have had land in Rasteau since 1980. New growth in one of their two biodynamically-farmed parcels.

And oyster shells in their vineyards.

Elodie Balme

Julie Paolucci and Nicolas Brès, Domaine La Luminaille

Robert Laurent, Domaine Combe Julière

Images of Côtes du Vivarais

Alain Testut, president of AOC Côtes du Vivarais

David-Alexandre Gallety, Domaine Gallety

Domaine Gallety

Rachel and Raphaël Pommier, Domaine de Notre Dame de Cousignac

The chapel of Notre Dame de Cousignac

Sébastien Etienne, grape grower for UVICA

Beyond Burgundy: The New World finds its way with Pinot Noir and Chardonnay

From big-fruit ‘varietal wines’ to joyless Burgundy-lite pastiches, the New World has taken a while to get its head around Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. But there is a third way – and it’s working.

What does New World Chardonnay taste like? What about classic New World Pinot Noir? It’s a question that was easier to answer in the 1990s, when the ‘international style’ was easy to spot among leaner, more savoury Burgundies.

But since the mid-2000s, the major New World countries have been chasing a more elegant expression of these most quintessentially food-friendly grape varieties. Today the lines have become blurred with their Old World counterparts. But what has driven this rapid stylistic evolution?

Have we gained ‘Burgundian’ finesse the world over at the price of diversity? And does the increased focus on terroir herald the end of a discernible ‘New World’ style?

Grape expectations

Burgundy is the benchmark, as the origin of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. It has been the heartland of these grapes for two thousand years and it is home to 1,200 delineated ‘climats’. Some, such as Clos de Bèze in Gevrey-Chambertin, were referenced as far back as the 7th century. For an industry that fetishises provenance and heritage, this is stuff money can’t buy.

And speaking of money, at the top end, the Côte d’Or enjoys some of the highest price tags of all. That’s as it should be. In terms of these two grape varieties, the best of Burgundy is yet to be equalled. If you make Chardonnay and Pinot Noir anywhere in the world, it must be hard to put Burgundy out of your head entirely.

All wine regions evolve, but ancient ones such as Burgundy with rigid appellation systems and longstanding traditions do so very slowly. This has been the New World’s major advantage and to some extent its biggest enemy. Producers are relatively free to experiment and change course to accommodate shifting consumer tastes and fashions. It’s the rate of evolution of these two key varieties outside France over the past 25 years that is most extraordinary, however, and most consumers are still catching up.

‘It’s no doubt that New World Chardonnay, in its previous guise, kickstarted a wine revolution,’ says Ronan Sayburn MS of 67 Pall Mall. ‘New World Chardonnay arrived and offered rich, ripe sunshine-in-a-bottle, that was inexpensive and easy to understand.

‘With pictures of surfboards and beaches on the labels rather than old castles, they offered accessible and fun wines without pretension.’

New World Pinot Noir was similarly easy to enjoy, being sweeter, oakier and friendlier than consumers had encountered before. Tim Lovett, senior winemaker at Leeuwin Estate in Western Australia, has observed wine styles changing over time. Although there has always been a variety of interpretations of Chardonnay across his native country, he says that in the late 90s the prevailing one was full-bodied, noticeably oaky and very ripe in flavour profile.

These wines found favour with certain critics at the time, but gradually winemakers and wine lovers bored of them, finding them tiring to drink and lacking in finesse. By the early 2000s, a move towards a fresher, more drinkable style was underway. For Chardonnay, winemaking held the key; for Pinot Noir, the answer was found in the vineyard.

Lovett explains that Western Australian producers started picking their Chardonnay earlier, meaning lower sugar levels (so less potential alcohol) and higher natural acidity. To this, he adds higher turbidity (more suspended solid matter) in the juice pre-fermentation and malolactic fermentation as drivers of a more contemporary style.

David Ramey of Ramey Wine Cellars in Sonoma puts the transformation of Californian Chardonnay down to two principal movements: ‘The triumph of the Burgundian method’ and a ‘march to the coast’. Since his first vintage in 1978, winemaking in California has changed radically towards a more Burgundian style. Previously there was overnight skin contact, the juice was racked off the lees, malolactic fermentation was blocked, the wines were overoaked and sterile filtered. These are all things he avoids today.

Two other Chardonnay winemaking techniques that Ramey singles out that have made a big difference are juice browning and whole-cluster fermentation, both of which he claims to have pioneered in California. Juice browning is the practice of exposing grape juice to oxygen before fermentation – alarmingly the juice goes from green to a murky brown as certain compounds oxidise (rather like a cut apple), but the wine runs clear after fermentation.

For him it produces a finer, paler wine that’s lower in tannin. He started using whole clusters back in 1987, which he believes lead to greater delicacy and ageing potential. When Ramey says the ‘march to the coast’, he refers to growing grapes closer to the ocean, particularly at the wind gaps – breaks in coastal ridgeways that draw in cool air and fog from the ocean. These moderate the climate and help to produce more elegant wines. Interestingly, Ramey now believes that Napa Valley is too hot to grow Chardonnay successfully.

Elegance through viticulture

Finding the right sites, particularly where temperature is moderated by altitude, aspect or climate, was the key for many in the evolution of Pinot Noir. Gordon Newton-Johnson has been making wine at the family winery in Hemel-en-Aarde in South Africa since the mid-90s. South African Pinot Noir at that time wasn’t terribly inspiring. ‘Some wines were insipid, others over-extracted or blended, and the muddled message held little to no terroir expression at all,’ Newton-Johnson says. This, though, wasn’t just down to site.

‘A major catalyst for change was the introduction of new, quality vine material, especially those of Raymond Bernard’s “Dijon clones”,’ he says. ‘The change in Pinot Noir was immediate, providing a much-improved varietal base from which to work. ‘A new generation of producers were naturally drawn in to the vineyard on seeing the limitations of the winery. There was much better exposure to international benchmarks and creating networks, so the knowledge base blossomed.’

It’s not just plant material and site selection that made a difference in terms of New World viticulture. Exposure to different winemaking cultures has also been crucial.

Paul Pujol of Prophet’s Rock in Central Otago, New Zealand, spent six years working abroad, including stints in Alsace, Sancerre, the Languedoc and Burgundy. The modern wine industry in New Zealand only dates back to the 1970s, so to work in regions that span centuries was eye-opening for him.

‘There is a tremendous amount to learn from working in different places,’ says Pujol. ‘Some is technical and some is cultural, or the human element, which is also very important. You see a different mindset when a vigneron is from a multi-generational producer, which is so common in France. They are so conscious of their small part in a business that runs both before and after them.’

It’s not just plant material and site selection that made a difference in terms of New World viticulture. Exposure to different winemaking cultures has also been crucial

‘In the winery, the same range of techniques are available anywhere,’ he explains. ‘But what you notice most in France is how winemakers have adapted what they do to the vineyards they work with, rather than imposing a style or range of techniques on a site.

‘This sensitivity to exploring and finding out how to express a site in the purest sense, without an overriding winemaking signature, is one of the greatest lessons I took from my time in France.’

From sun to site

As consumer tastes moved to a more elegant style of wine in the 2000s, it’s no surprise that those producers of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, free from the constraints of tight appellation legislation, looked towards the classics for inspiration. This inevitably led to a proliferation of more Burgundian styles, but there’s been another movement since then that has further contributed a sense of finesse.

‘With the advent of non-interventionism in winemaking,’ says Newton-Johnson, ‘I feel many producers began to see glimpses of real identity from their vineyard sites. I think it’s fair to say that our philosophy is more Burgundian than 20 years ago.

‘I believe our most compelling wines are a consequence of where they have been planted, and that has been progressive in discovering our identity. Regarding these grapes as a medium of interpretation rather than a variety opens a whole new realm of potential.’

Hands-off production methods have been adopted more and more by leading estates worldwide, often with the aim of accentuating site over grape variety, and the result is often wines with more subtlety and character – it produces elegant wines, but wines with a local elegance rather than a Burgundian one.

These relatively restrained New World wines focussing on finesse, balance and terroir were often overlooked by the critics of the day, who were still in thrall to ‘big flavour’. It took collective movements such as the Swartland Revolution in South Africa, from 2010 to 2015, and particularly Rajat Parr and Jasmine Hirsch’s In Pursuit of Balance in California, from 2011 to 2016, to push these styles into the collective consciousness.

Andres Ituarte of Le Coq d’Argent agrees. ‘I don’t think New World wines are becoming more Burgundian, they are just becoming better balanced,’ he says. ‘Look back at that Leeuwin Estate Art Series Chardonnay. It’s no less woody than 25 years ago, but it is way more zippy and elegant.

‘With Pinot and Chardonnay, we are seeing restraint being used in the winery because of the understanding in the vineyards. The New World is just catching up with the Old.’

The end of the New World as we know it

Describing a New World wine as ‘Burgundian’ may once have been received positively by winemakers around the world, but as they endeavour to express their wines’ own local character, it might now be considered less than flattering. Adelaide Hills, Martinborough, Sonoma and Walker Bay are, after all, highly contrasting terroirs.

The push for elegance and finesse can sometimes go too far, however, as certain winemakers compete for the most delicate, structural style – a practice that’s been described in some parts as ‘reverse willy-waving’. Ronan Sayburn encountered this style recently in Australia.

‘I was surprised by some of the Chardonnay being far too lean and acidic, lacking fruit and body,’ he says. ‘[One was] described by one winemaker as ‘fishbone Chardonnay’, the implication being there was no flesh or meat to the wine, just structure.

‘Care needs to be taken with going too lean. New World Chardonnay became popular because of its vivacity and ripeness; elegance is great as long as the wine has flavour and as long as it remains fun. That’s why we liked it in the first place.’

David Ramey recognises a similar phenomenon in California. ‘The middle ground in California is what’s happening now – not the overblown styles, not the “12.5% and no new oak” – but the 13.5% wines without excess new oak. That’s what’s happening in California and it’s often better than white Burgundy and half the price.’

For UK sommeliers, such as Valentin Radosav at Gymkhana, price is increasingly a concern. ‘Burgundy is very expensive. Each year the price goes higher and the quality remains the same,’ he says.

‘This pushed me to look for alternatives from other countries like Portugal, Central Europe, South America, South Africa. I am a huge fan of Chardonnay (Restless River) and Pinot Noir (The Drift Farm) from South Africa. They offer great value for money and are wines with a lovely ripeness and complexity.’

As Chardonnay and Pinot Noir from the New World gain in finesse, increasingly they can do the same job as many Burgundies on a wine list – but at considerably lower prices. Many casual wine drinkers in the UK still associate New World Pinot Noir and Chardonnay with a ripe, high-alcohol, oaky approach. Some wine professionals turn their noses up at these styles, though their popularity persists.

Though these versions are on the way out, they’re still easy enough to track down if they resonate with your clientele or work with your cuisine. It’s hard to imagine a time when Burgundy will no longer be the global benchmark for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, varieties that express terroir like few others. Warm climate New World iterations made a huge impact in the 90s and ‘classic’ examples still have their fans today. But their rapid evolution still has much to thank the motherland for: practical viticulture and vinification techniques, quality plant material and its role as a cultural, even spiritual, guiding light.

Increasingly, though, New World regions and sub-regions are finding the confidence to follow what the land dictates, rather than chasing the tastes of consumers and critics. In doing so, we’ve witnessed the gradual relinquishment of the ‘international style’ in favour of unique expressions of terroir. The future of each region will increasingly diverge as a result. In other words, rather than the end, this is really the beginning.

First published in Imbibe on-trade magazine.

Images of Lirac, March 2019

Eric Pfifferling, Domaine L'Anglore

Eric Pfifferling, Domaine L'Anglore

Carbonic maceration lessons with Eric

Carbonic maceration lessons with Eric

Ermitage de la Sainte Baume

Ermitage de la Sainte Baume

Plateau de Vallongue, Lirac

Plateau de Vallongue, Lirac

Limestone pebbles, Saint-Laurent-Les-Arbres

Limestone pebbles, Saint-Laurent-Les-Arbres

Rodolphe des Pins, Domaine de Montfaucon

Rodolphe des Pins, Domaine de Montfaucon

Bush vines planted in 1870, Domaine de Montfaucon

Bush vines planted in 1870, Domaine de Montfaucon

Images of the Luberon, February 2019

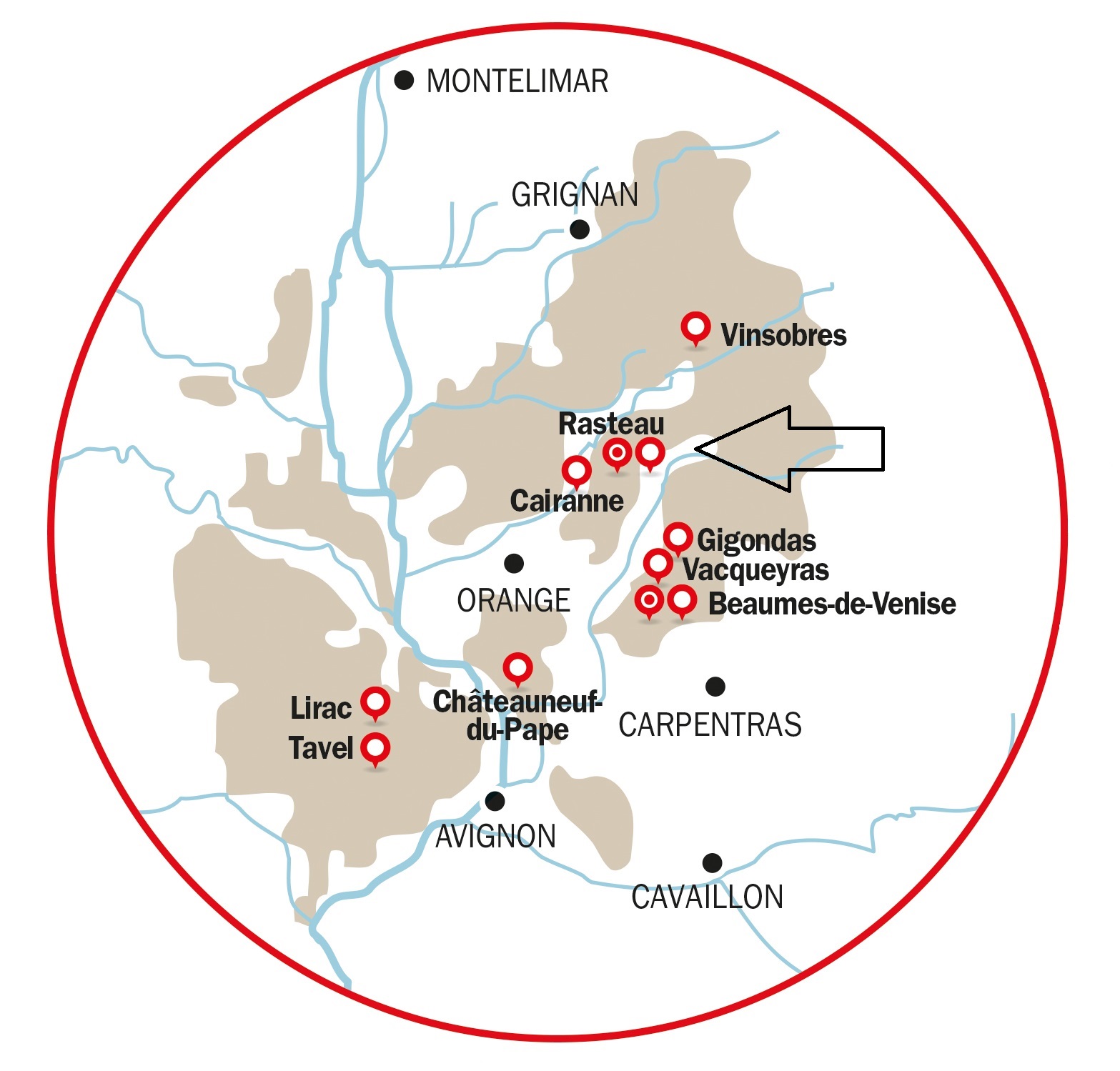

The kingdom of the blind

Most wine professionals have a story of when they aced a blind tasting, a well-worn tale of olfactory deduction that would have Sherlock Holmes slack-jawed in amazement. It inevitably concludes with a self-deprecating comment along the lines of ‘normally I get it completely wrong of course’ in the hope that the taster can both impress and not come across as a shameless show-off. Blind tasting is not only an entertaining sport; it’s widely accepted as the best way to run major wine competitions and it’s often the way that consumers prefer critics to taste wine. When it comes to wine criticism, however, blind isn’t always best.

There are some undeniable benefits to blind tasting. Removing the producer’s name and any indication of market value from the equation gives a taster the freedom to assess what’s in the glass with greater objectivity. It makes it easier to reward little-known or relatively modest estates when they excel, and simpler to reprimand the big names when they slip up – two of the most important functions of any wine critic. Blind tasting makes the critic focus on every bottle; there is no space for laziness or sloppiness. And it continually hones the skill and knowledge of the taster in the process which is beneficial for the critic, the producer and the reader.

It’s worth noting that double-blind tastings, where you don’t even know a wine’s country of origin, aren’t terribly instructive. It makes it impossible to judge a fundamental characteristic of any great wine: typicity. How can you tell if a wine is a good example of its type when you don’t have the slightest clue what it is? When tasting blind, it’s important to taste within a defined style.

Blind tasting does have its drawbacks however. The most irritating – but least discussed – downside is the unpalatable fact that wine doesn’t always behave the way it’s meant to. (If this weren’t a fact, there’d be far fewer wine merchants around selling disappointing Burgundy.) Some wines show inexplicably well on the day of tasting; others show peculiarly badly. It can be attributed to any number of factors: the wine going through a ‘closed’ or ‘dumb’ period, the critic’s mood, even atmospheric pressure or tasting on a root day… But often there’s no obvious explanation.

Also, critics make mistakes – and it’s more common to reach the wrong destination when you’re travelling blind, with no landmarks or directions to lead the way. Until we can design a more reliable instrument than the tongue, we will have to rely on men and women to critique wines, and that means having to accept a degree of human error. Some critics would never admit to such a thing in public; professionally it’s safer to project an image of infallibility. But in private, most will admit to calling it wrong from time to time, particularly when tasting blind.

Critics of blind tasting state, quite correctly, that it bears no relation to how most normal winelovers approach a bottle of wine. Tasting a wine when you’re aware of its identity is a more natural and less convoluted way to go about it. And, after all, the enjoyment and value of a wine isn’t just about what’s in the glass.

Crucially, when judging a wine, knowing its identity gives you context. When you know the producer, you can see how the wine in question compares to previous vintages, if it’s above or below their usual standard, if there’s a change of style or direction... Importantly, you can make a judgement regarding value for money. It also lets you take into account outlying styles that flirt with winemaking faults which could risk getting thrown out of blind tastings.

There’s a danger however of critics giving a wine ‘the benefit of the doubt’ when they can see the label on the bottle but what’s inside isn’t performing as they’d expect. In this way, sighted tastings can unjustly end up favouring the status quo – the longest established, most revered producers tend to come out top. If there’s any doubt over how a wine is showing, it’s better all round for the wine to be removed from the tasting and looked at again at a later date.

Blind and non-blind tastings have their own particular advantages and disadvantages. As always in wine, it’s best not to be dogmatic: I’d argue that the way to get the best advice to the prospective wine buyer it to combine the two. Firstly, to taste wines blind, to mitigate confirmation bias as much as possible. Then to reveal the identities of the wines to see if this sheds any light that would further inform the decision-making process for buyers. Knowing the wine’s track record would also help refine drinking windows.

To some critics, this might sound like ‘cheating’ – adding in commentary to a tasting note after their judgement has been passed. But it’s important for tasters to remember that the process isn’t about them. It’s about getting the best possible advice, by whatever means, to whomever is considering spending their hard-earned money on a case of wine.

Neither blind nor sighted tasting is perfect when it comes to wine criticism. It’s a well-known fact that the most reliable way to grade a flight of wines is to drink them with a bunch of wine-loving friends over dinner and see which ones get finished first. But when that’s not possible, tasting with one eye open could be the best option.

Image © Chris Nguyen via Unsplash

First published in timatkin.com.

Images of Vinsobres, Feburary 2019

Images of Séguret, February 2019